The Nevada Legislature convened July 8 for its 31st special session to consider budget cut recommendations, including those from various state agencies looking to collectively help offset a $1.15 billion projected state budget shortfall announced last week by Gov. Steve Sisolak’s Finance Office.

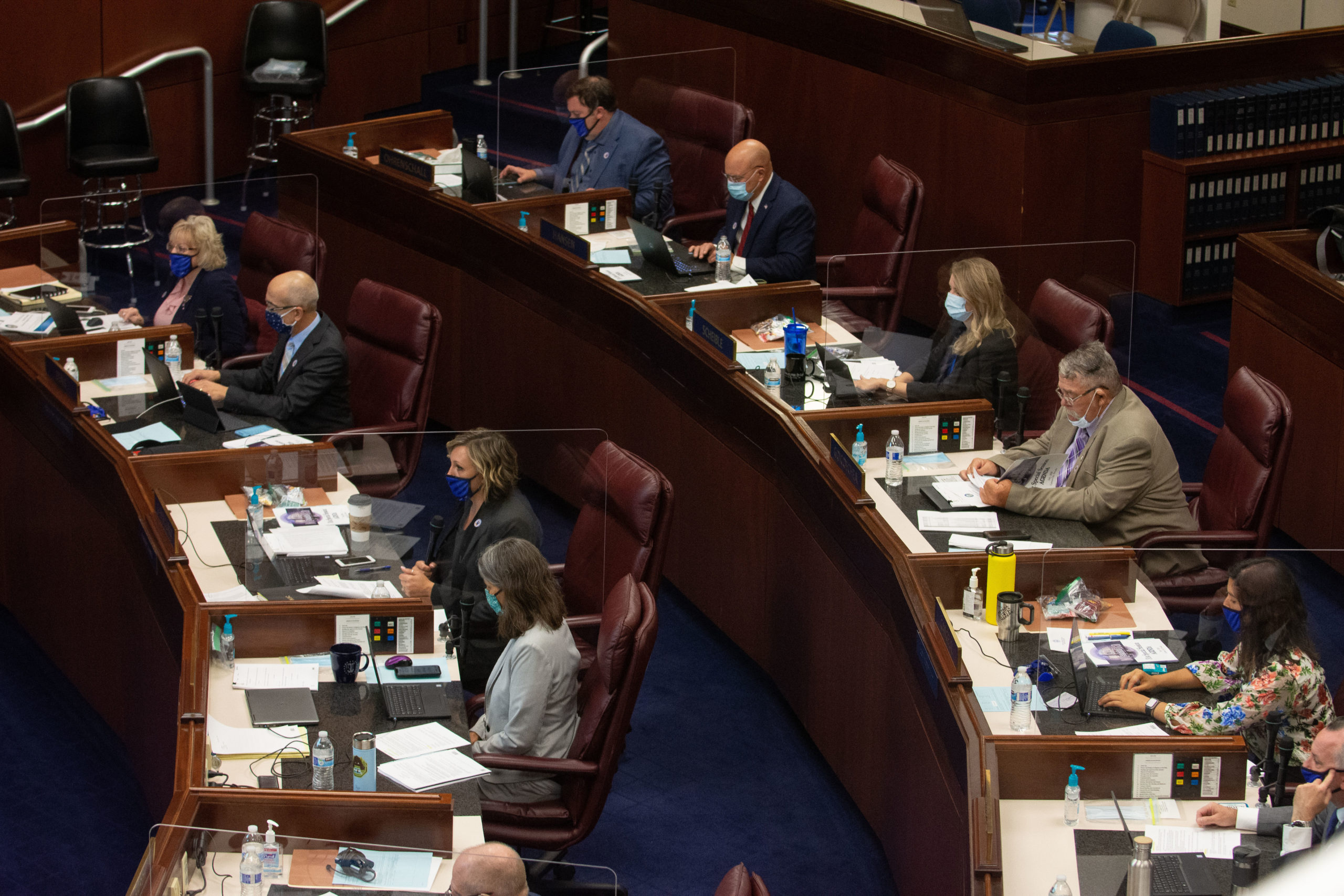

No lobbyists were allowed in the building, and legislators strictly observed social distance rules in place as a result of the ongoing global COVID-19 pandemic. Journalists’ access was strictly limited, with one reporter allowed in each legislative chamber at a time—and a single pool photographer assigned to cover the duration of the session.

After taking public comment from callers who overwhelmingly asked the Assembly to consider any possible alternatives to steep cuts proposed to public education in Nevada, legislators in that body heard from Susan Brown, director of the Governor’s Finance Office, who gave an overview of recommended budget cuts to legislatively-approved spending across the board, before taking questions.

Brown’s overview for legislators discussed the governor’s proposals, to include more than $500 million in cuts to agency budgets, reversions from contingency funds and furlough days for state workers.

Brown was quick in covering the plan released Monday by the governor’s office, which calls for measures like transferring money from other sources to the General Fund—including around $84 million from the Tax Bond Account, Bond Redemption Account and Health Nevada Fund. The proposal also called for a $24 million reduction in one-time appropriations and for moving $26 million out of restricted contingency funds.

The plan also includes 12 furlough days for state workers, the freezing of merit pay increases to their salaries and the continued vacancy of some 700 state positions.

It also recommends a 90-day tax amnesty to allow residents to pay any applicable overdue taxes without paying penalties. A similar measure was taken to allow Nevadans to get current on delinquent taxes during the Great Recession.

It was a lot to cover after a slow start to the special session, which began with public comment followed by a recess that was intended to last fewer than 20 minutes but exceeded an hour. When Brown had finished her summary of the proposed budget cuts, assembly members had many questions—many of them noting that the pace with which she’d covered information had left them confused. In asking their questions of Brown, assembly members—including Clark County Democrat Maggie Carlton—pointed out that members who don’t sit on certain committees like Ways and Means (which she chairs) or the Interim Finance Committee might not fully understand some of the discussed appropriations.

Republican Assemblymember Robin Titus of Churchill County asked Brown how the “blanket furlough” decision of 12 days for state workers was made and if it posed a risk of actually costing the state money as a result of a possible loss of federal funds used to offset their wages.

Brown explained that an “exception process” was intended that would allow agencies to request exemptions from furloughs. There is some flexibility she said, and decisions for some agencies will have to be made on a case-by-case basis.

Brown also told legislators about various uses to which CARES Act funding may be put by Nevada, including the purchase of necessary safety items like personal protective equipment, disinfectant and Kleenex, the installment of plexiglass barriers in offices and even the wages of employees like public safety officers.

After several hours of testimony and Q&A, legislators had requested that additional information and datasets concerning a number of items from Brown and her staff be delivered to them later.

The Assembly then took up its hearing on matters related to public education in the state. Public schools and the Nevada Department of Education were asked to find more than $180 million to cut from their spending.

Contentious discussions on K-12 education

Technical issues on the side of NDE Superintendent Jhone Ebert at times made the discussion on public education difficult. Her video and audio connections were both spotty as she gave her presentation to the Assembly before turning things over to Rebecca Feiden, executive director for State Public Charter School Authority, and three of the state’s 17 school district superintendents—Jesus Jara of Clark County, Summer Stephens of Churchill County and Kristen McNeill from Washoe County.

The four gave their own presentations and then joined Ebert in answering legislators’ questions—of which there were many, particularly centering on ensuring equity in the process of reopening schools.

Several legislators expressed their concern for programs like Nevada’s Read by Grade Three initiative.

Assemblymember William McCurdy (D-Clark County) noted cuts to Read by Grade Three and other programs, saying, “We’re cutting from Title 1 schools,” and asking how it will affect the state’s most vulnerable children.

“Any cuts affect our children,” Ebert said. “All of these cuts will affect our children.”

McCurdy went on to question, “How will we attract teachers to come to these Title 1 schools? How will these kids be able to compete as they get older?”

Jara said in his district they’d been working to increase funding to Title 1 schools and were working with their teachers’ union bargaining partners to ensure talented teachers were recruited to Title I schools.

In response to a question about why Gifted and Talented Program funding was being preserved while programs for some vulnerable student populations were not, Ebert gave an explanation in which she said G&T-enrolled students are likely to drop out if not provided with a challenging enough learning environment. There is some contention among education researchers as to whether or not this is actually the case.

Assemblymember Heidi Swank (D-Clark County) asked Ebert what kind of cuts were being made to the salaries of “the upper echelons” within her department. Noting that it has often been said of Nevadans that we’re all in this together, she asked, “What is everyone giving up on this?”

Ebert explained that people in her department are subject to the state’s 12-day furlough policy—marking about a five percent cut to wages for employees.

Jara, Stephens and McNeill had fewer details on how much of a pay cut might be seen by administrators in their districts—though McNeill pointed out that upon recently starting as superintendent with the school district, she gave back $30,000—roughly 10 percent of her salary—for the next fiscal year.

McNeill was told one of the disadvantages of her not being in the chambers with the legislators was that she missed the applause they gave her in response.

Assembly member Swank pushed back against Jara and asked for clear numbers or a projection of how much top administrators with CCSD might expect to see cut from their salaries.

Jara said those figures would have to wait but noted that his district froze all central office positions. They’ve not hired any positions that don’t directly affect the classroom for the last two years.

Swank continued, saying she had a friend who owned a company where all of the top leaders took a 50 percent pay cut at the beginning of the pandemic to avoid laying off staff. Some folks working in Nevada’s public schools and the NDE make a good deal of money and could give it back, like the superintendent from Washoe, she said.

Republican Assemblymember Alexis Hansen—who represents Esmeralda, Humboldt, Lander, Mineral and Pershing Counties as well as parts of Nye and Washoe—asked the three district superintendents if a “hold harmless” agreement should be considered and if it might relieve their concerns over navigating potential costs of reopening.

(A hold harmless agreement is a clause or a statement in a legal contract that absolves one or both parties of legal liability for any injuries or damage suffered by the party signing the contract. In this case, students would be holding their districts harmless should they return to them only to contract the coronavirus.)

All three district superintendents and Feiden of the Charter School Authority said yes to this.

Several assembly members expressed appreciation for the fact that the state’s Distributive Schools Account (DSA), from which funds are doled out to the various districts, will remain intact but questioned how decisions were made when selecting areas from which to cut.

Assemblymember Brittney Miller (D-Clark County) questioned how much is spent by the state and various school districts on contracts with testing companies for standardized testing but was told by Ebert that much of statewide testing is funded through federal dollars.

As the hour neared 6 p.m., and with a discussion of the Nevada System of Higher Education still to come that evening, Teresa Benitez-Thompson (D-Washoe County) said she wanted to make a few comments rather than ask questions.

She questioned why plans for reopening continued to allocate funds to nonprofit partnerships and programs with groups from outside of the schools, noting that funds set aside for the Jobs for America’s Graduates program—could be used to fund things like the Teach Nevada Scholarship, something that’s currently on the chopping block.

She, like others, said maintaining the DSA was a win for Nevada schools.

“When I look at this budget, the piece that makes me happy…is that we are maintaining the Distributive School Account,” Benitez-Thompson said, adding that she’s pleased that measures taken last legislative session, like increases to per-pupil funding, will be maintained.

“It’s a bright point in the cruddy $1.2 billion in cuts we have to make,” she said.